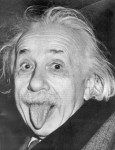

…siamo della stessa famiglia. Einstein ci spiega come:

…We all are part of the same lineage. Einstein tells us why:

1. Follow Your Curiosity: “I have no special talent. I am only passionately curious.”

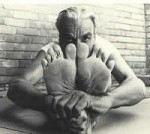

My Journey into Yoga. BKS Iyengar.

The 94-year-old iconic yogacharya B K S Iyengar walks down memory lane, going right back to when he started.

I am neither a Sanskrit scholar nor a philosopher; am purely an ardent student of yoga, involved insadhana for nearly 80 years, exploring its depth in order to gain and understand rightly the beauty and majesty of the vast ocean of yogic knowledge along with experiential wisdom. My uninterrupted sadhana has not only burnt all types of impediments and obstacles, it has also kindled the flame of wisdom within.

A great yoga master, T Krishnamacharya, initiated me into yoga at 14. Being so young, I never had the privilege of theoretical tutelage from his storehouse of knowledge.

I had been bedridden from birth with influenza, malaria, typhoid and tuberculosis, so it was to recover my health that my Guru initiated me into yoga. Though I questioned him a few times on the finer aspects of yoga, he would avoid or ignore these, perhaps because I was unschooled in Sanskrit, or it may have been my age that he considered a bar for delving deeper into yoga. Whatever knowledge I gained on yoga was through his public lectures. Within two years of training, he sent me to teach at Dharwar, in Karnataka, and Pune, in Maharashtra.

Uncharted path

Thrust upon me, this occupation was a God-given opportunity. I was propelled into the subject and committing myself to it, progressed in my personal life as well as in practice. Since I’d been left isolated and unsupported to tread an uncharted path, I had to practise, teach and find the means to learn about the principles of yoga. In dire poverty, this was no easy task. I was not only a novice in the field, I was also physically and mentally disadvantaged with setbacks in health.

Living in Pune, it was impossible for me to get help from scholars as I did not know a word of the local language, but also there were none acquainted with the subject. With my salary, I could not afford books. I was also under contract to teach for all hours of the day – something I’d accepted as my Guru’s order also for my survival. I would trace the asanas that revived me, rendering me fit the next day. I began to revere the subject only after 12 years of practice and teaching….

Reflex actions are instinctive. They are innate responses to natural skilful tendencies. I began analysing these natural tendencies that occurred in my sadhana with my own intuitive thoughts, to attain the experience.

In Hindu temples, priests anoint and rub oil on idols as part of religious ceremonies. In my practice, I began to rub my body and mind with the aid of intelligence, for them to soak deep into all the vestments of self from annamaya kosha to atmamaya kosha, and feel the presence and flow of the flame of awareness in all my nerves, fibres, muscles, joints and cells.

I began to visit a public library in Pune and spent hours studying the few yogic books that were available there. I would find it extremely hard to grasp what was written. The language was too ‘high’, and beyond my raw, ruffled and restless mind and intellect to grasp.

Perhaps, it was my good fortune that I could not learn the Yogasutras in a formal or traditional way. Whenever I referred to them, they appeared too terse to understand, as they are condensed, coded and succinct. After years of sadhana and tapas, without reference to the Yogasutras, but with the aid of the Hatha Yoga Pradipika and chapters of the Bhagwad Gita where Krishna deals with the practice of yoga, I began to gain some basic knowledge on the subject. I also read some contemporary translations and commentaries on the Yogasutras.

Experiential learning

Through sadhananubhava and with time, I began to see shortcomings and contradictions in these works. This encouraged me to study the Yogasutras carefully on my own, along with classical commentaries, keeping in mind bhavana or experiential feelings of my own sadhana. The explanations and commentaries were more academic and scholarly, and mostly under the influence of respective Vedantic schools of thought of commentators. Though they offered an overall view of yoga philosophy, their means and ways of practical adaptation appeared limited.

Next, I tried to do a comparative and analytical study of the Yogasutras and teachings and views of the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, the Gita and the Yoga Upanishads. I used my body, mind, intelligence and awareness in sadhana as a laboratory. Finally, this helped me grasp gradually the essence of the Yogasutras of Patanjali.

We need to look at Patanjali’s masterpiece as a compendium of the entire literary heritage of classical India. It is not a revelation like the Vedas and classical music, yet it conveys the essence and depth of sacred scriptures. Its masterful composition and rhythm brings it under the category of kavya or poetic literature, whereas it may be considered as a synthesis of all smriti or remembered literature, as itihasa – like those of the Mahabharata and Ramayana – and all major and minor puranas.

Infinite knowledge

The last shloka of the Gita’s third chapter says that the Self is superior to self and intelligence. Krishna advises Arjuna to control the inflated ego and steady mind movements by cultivating indifference to lust, anger, greed, infatuation and envy. With all these shortcomings in me, in earlier stages, by the grace of destiny and my sadhana, I could gain control as well as have an open mind to learn.

I must emphasise that, with my experience and belief, students of yoga read and study the Gita well before undertaking study of Patanjali’s Yogasutras.

Knowledge is infinite and eternal, but human thoughts are in the field of the finite. The infinite is hidden in the finite, and the finite is hidden in the infinite. In my sadhana, I tried to explore the infinitesimal particles in the finite body. This helped me understand the Yogasutras with clarity.

Each day, the moment I begin my sadhana, my entire being is transformed. My mind extends and expands into vastness. It is into that inner limitless space that I begin to delve. Thus I find myself closely connecting to the Yogasutras, and I begin to feel their values coming directly in my sadhana.

WE, YOGARUNNERS, TOO, IN RUNNING WITH YOGA, MEDITATE IN MOTION AND FIND THE UNITY, THE ALIGNMENT THAT MAKES US RUN LIGHT AND INJURY FREE TO THE FINISH. ON THE MAT AND ON THE RUN IN “EFFORTLESS EFFORT”.

Namasté